‘Boys Love’ manga presents gay men for the pleasure of straight women – so why does it represent both so badly?

[Contains spoilers for ‘Ten Count’ and ‘Raising a Bat’.]

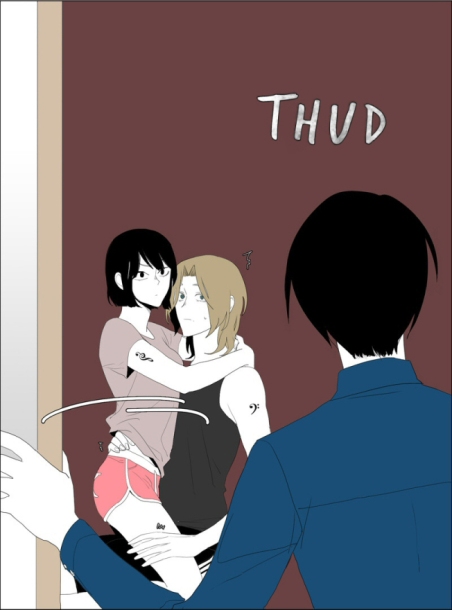

In hit anime series, Ouran High School Host Club, twin brothers Kaoru and Hikari always make sure to treat their female guests at the titular club to quite a show of “brotherly love”.

For viewers popping their proverbial anime cherry, these scenes must be a bit of a culture shock. For those more familiar, it translates as both serving and gently mocking the shounen-ai (‘boys love’ or BL) genre; fulfilling its target audience’s expectations whilst cheekily representing them as easily manipulated girls with nothing better to do than fawn over bishounen (‘beautiful men’).

As a life-long otaku with a soft spot for said beautiful fictional men, I can’t say that I don’t see a little of myself in the squealing guests of the Host Club and niether do I see anything wrong with it. The level of eye-rolling that follows the success of things like Magic Mike or Fifty Shades of Grey or any other cultural product that caters unabashedly to female sexuality is getting pretty tedious.

I mean, Free! doesn’t exactly owe it’s success to the big cross-section of anime and professional swimming fans does it? Source: Giphy.

At the same time, I also know that BL is a genre unfortunately beset with complicated problems in the way it represents gender and sexuality.

The fact that the majority of BL stories are created and read by women binds the genre in both positive and negative baggage. On the negative side, far too many stories that occupy this particular genre of storytelling promote unhealthy and harmfully unrealistic depictions of gay men through a female heteronormative gaze. This is especially true of ‘yaoi’ stories, a sub-genre of shounen-ai that features more sexually explicit content, and one in which gay men are even more in danger of being objectified and fetishized by this gaze.

A page from popular BL manga, Kuroneko Kareshi no Aishikata, by Ayane Ukyou.

There’s also, I’ve noticed, a perpetual conflict between BL character’s sexuality being unfairly dominant in defining their personality, yet strangely absent in their lifestyles. Even the out and proud BL characters who are doggedly obsessive in their romantic pursuit of other men hardly ever self-define – verbally or otherwise – their own sexual preference by name. More to the point, I have yet to see one of these characters to go a gay club or Pride parade. Instead, they always seem totally isolated from their own community – a community that is notoriously familial, IRL. In these tiny, pocket universes dedicated to man-on-man action, the ‘G’ word seems either be taboo or redundant.

If we go with the latter description, you could argue there’s something progressive in enjoying romance stories without ‘seeing’ gender. As Lin-Manuel Miranda poetically put it: “Love is love is love is love,” after all. But, when we’re talking about BL, we know that’s simply not the case. It’s right there in the name after all: boys love. And since heterosexual love stories are still a dime a dozen, there’s a kind of voyeur curiosity for the straight consumer attached to ones told from an LGBTQ perspective.

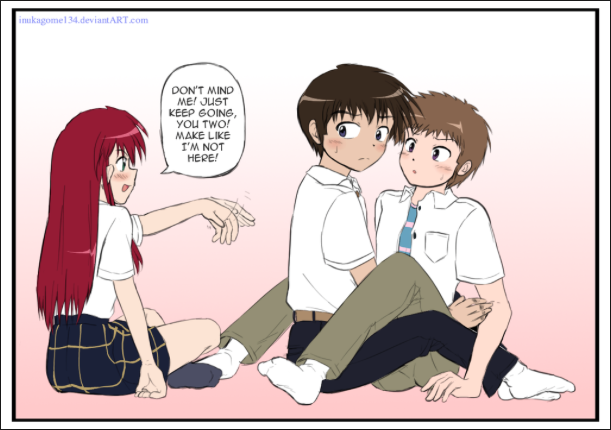

I wouldn’t ever use the word ‘regular’ to distinguish between heterosexual and homosexual relationships, but the right sentiment is there all the same. Source: Pinterest.

In fact, that ‘exotic’ aspect of BL’s appeal is also part of its fans’ defence of it. After all, so much of romantic fiction – particularly erotica like yaoi – operates within a realm of fantasy so great that their realism may as well be discussed alongside the The Lord of The Rings books. And as more women prefer to read erotic fiction rather than watch porn, thinking of BL in this context grants it more leeway to cater to women’s depoliticised fantasies of gay men rather than how they really are. It’s not a full exoneration as such, more of ‘reasonable doubt’ defence.

BL certainly contains some questionable depictions of gay men, but perhaps equally troubling is its representation – or often lack there of – women. This is also particularly strange for a genre that is so female-focussed from inception to readership. The literary world is still dominated by men and the comic book industry is no exception. For this reason alone, the space carved out by women in the Japanese market for shojo and shounen-ai decades ago was downright pioneering. Just read this extract from Mark MacWilliams’, Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime, for further proof:

“The production of Japanese comics has always revolved around men – male artists, editors, and publishers – and they reacted to yaoi comics with revulsion, which caused a sensation. The mass media criticised such stories as decadent and degenerate, using hyperbole to characterise these kinds of stories as a “violation” of manga. However, this issue of homosexuality also stimulated the industry creatively. Today, one can find many successful female artists and editors in Japan. The continuing popularity of yaoi comics also suggested that Japanese women are not shocked by gay themes.”

Knowing this revolutionary history of the genre, it seems surprisingly counter-intuitive that so many BL stories are so misogynistic in their tone and representation of women. Female creators too often either vastly underrepresent their own gender, or cast them as antagonistic forces standing in the way of ‘true’ male love. The latter of which I found to be a particularly troubling aspect while reading Takari Rihito’s Ten Count manga – one of the highest selling BL manga in Japan since 2014.

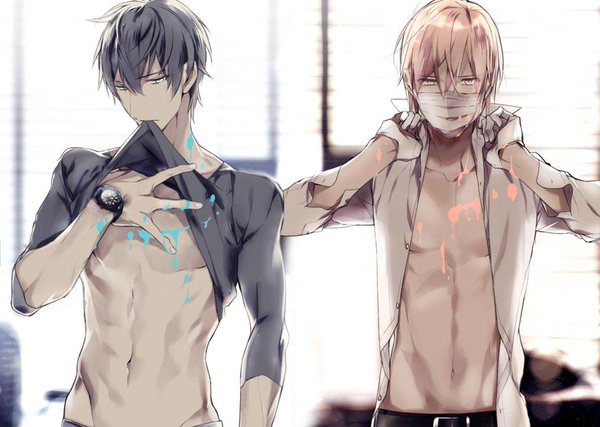

Cover art from volumes 1& 2 of Ten Count by Takari Rihito.

Ten Count could best be described as the yaoi market’s version of Fifty Shades of Grey, which would make shy and inexperienced protagonist ‘Shirotani Tadaomi’ [pictured right, above] its ‘Anastasia Steele’. Shirotani has been plagued by misophobia (a psychological fear of being contaminated by dirt) for almost his entire life, which also inadvertently suppressed the truth of his own sexuality. Suppressed that is, until he meets a tall, dark and handsome doctor named Kurose [pictured left, above], who just happens to specialise in treating psychosomatic illnesses, and vows to cure Shirotani.

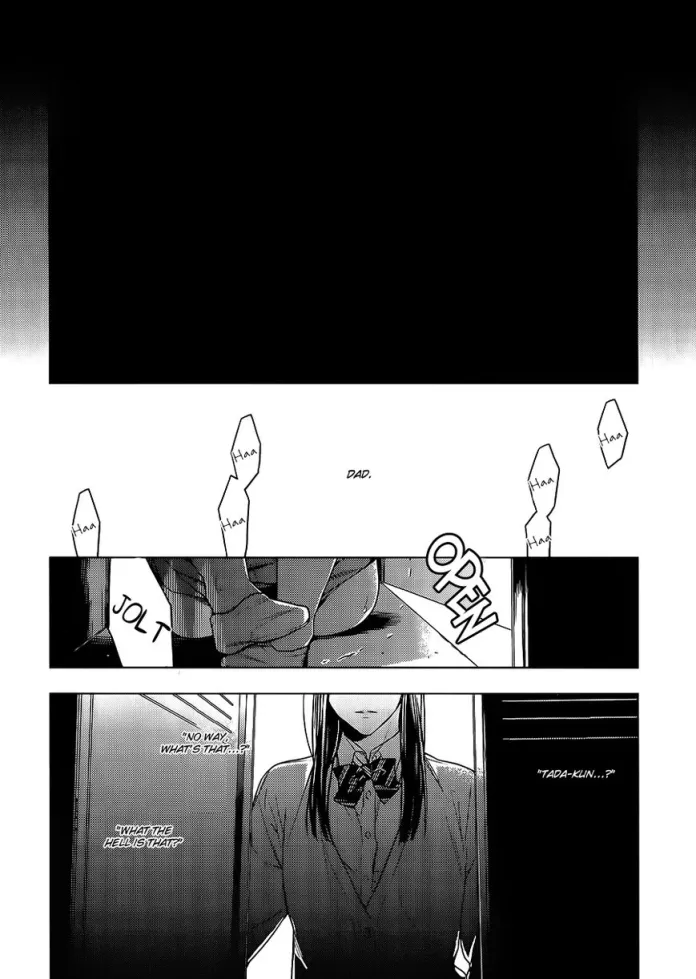

So far so yaoi, until it is revealed through flashback that the root of all Shirotani’s ails was… guess what? A woman! A woman by the name of Ueda, who – when Shirotani was a little boy – drove a wedge between him and his father (her school professor) by pursuing a sexual relationship with him. On one particularly traumatising occasion, Ueda tricks Shirotani into hiding in a closet while she has sex with his father. On the cusp of puberty, Shirotani feels confusingly aroused and tries to ‘relieve’ himself, which is the exact moment that Ueda pretends to discover him:

- 1.

- 2.

Shamed by Ueda, Shirotani desperately washes himself over and over again, unable to feel properly ‘clean’ after what happened. Subliminally, he starts to conflate arousal with dirtiness, becoming obsessively paranoid of any foreign contact from the outside world – especially human.

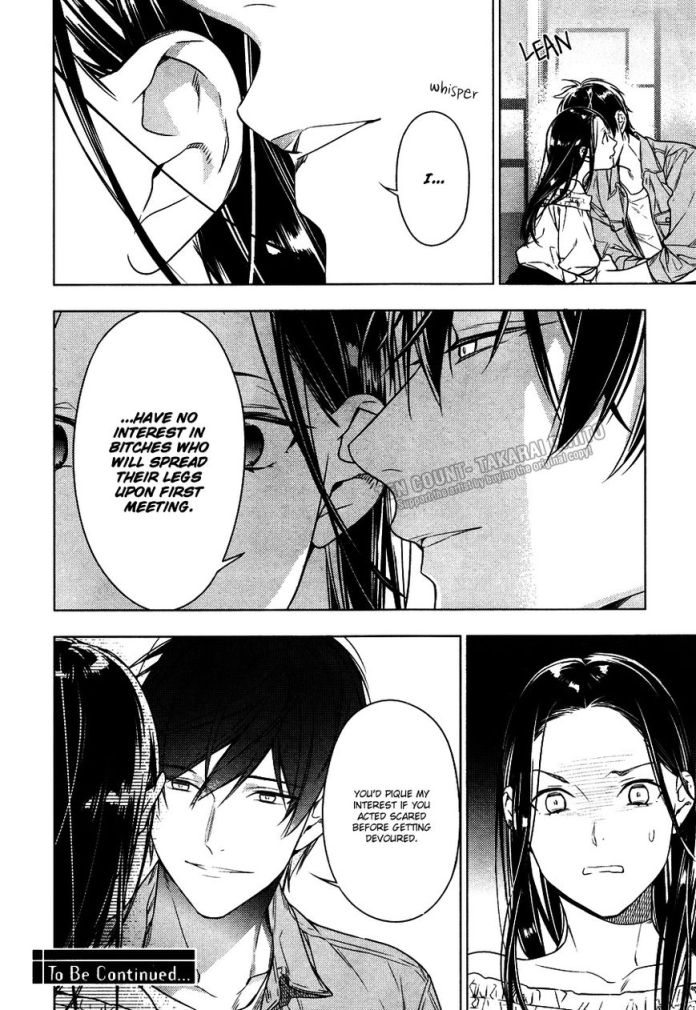

Equally troubling later on is Kurose’s treatment of Ueda in the present day, when – upon a chance encounter with him and Shirotani – Ueda antagonises Shirotani into storming out of the trio’s lunch date, and then tries to fruitlessly hit on Kurose. Kurose’s reaction to this unwanted attention is, um, well see for yourself:

Ouch.

Obviously Ueda is not a supposed to be a warm, sympathetic character in the slightest, and every melodrama needs its moustache-twirling villain… but is the slut-shaming really necessary? And why does the only female character in the entire story have to be characterised as a man-eating sociopath? Considering that gay and female culture often go together like PB and J, this hostile ‘battle of the sexes’ trope is yet another negative aspect of the genre that is weirdly inconsistent with reality.

Look, the truth is: I criticise because I care. Ten Count is a deliciously guilty pleasure to read, which is why this blemish on its otherwise stellar quality riled me so much. As a feminist and a fangirl, I want the media I love to do a better job at serving its fans, which is why I’m going to end on a more positive note.

Raising A Bat (Bagjwi Sayug) is a Korean webcomic (or ‘manhwa’) that puts a supernatural twist on the problematic ‘seme‘/’uke‘ (dominant/submissive) relationship dynamic that most BL falls into. ‘Park Min Gyeom’ [pictured left, below] suffers from a rare blood disease called hemochromatosis, meaning his blood absorbs too much iron forcing him to regularly donate to keep healthy. This condition makes him the perfect source of food for his classmate, ‘Kim Chun Sam’ [pictured right, below] – a half-vampire. I guess you could call it the BL answer to Twilight. Interestingly, mangaka (creator) “Jade” refuses to let their dynamic fall into the standard ‘prey/predator’ one that you’d expect. Human Min Gyeom is in fact the one who calls the shots, deciding when and where vampire Chun Sam is allowed to feed off him, while Chun Sam – the burlier of the pair – falls into a more submissive role, visually evidenced by the cover art:

Cover art for Raising a Bat by “Jade”.

Abused and abandoned by his father, Min Gyeom has had to grow up far too quickly with his younger half-sister being his only source of genuine affection. He’s guarded, plucky and full of self-loathing. Chun Sam, on the other hand, was born to a rich and loving vampire/human family and babied by a watchful mother (who also served as his food source [insert Freudian analysis here]). He’s sensitive, naïve and painfully shy. Things get even more complicated when the two start to develop romantic feelings for each other, with their emotional baggage blocking them from being able to healthily express this.

Not only does Raising a Bat manage to subvert the troubling seme/uke trope in an unexpected way, it features a cast of positively represented women in supporting roles, and even a self-defining bisexual male character (Jung Won Hyung) whom Min Gyeom pursues a dysfunctional relationship with. Even better, when Jung Won betrays Min Gyeom’s trust by ‘forgetting’ to tell him he has a girlfriend on the side, “Jade” is clear in placing the blame squarely on Jung Won rather than make an enemy out of his girlfriend.

Uh-oh…

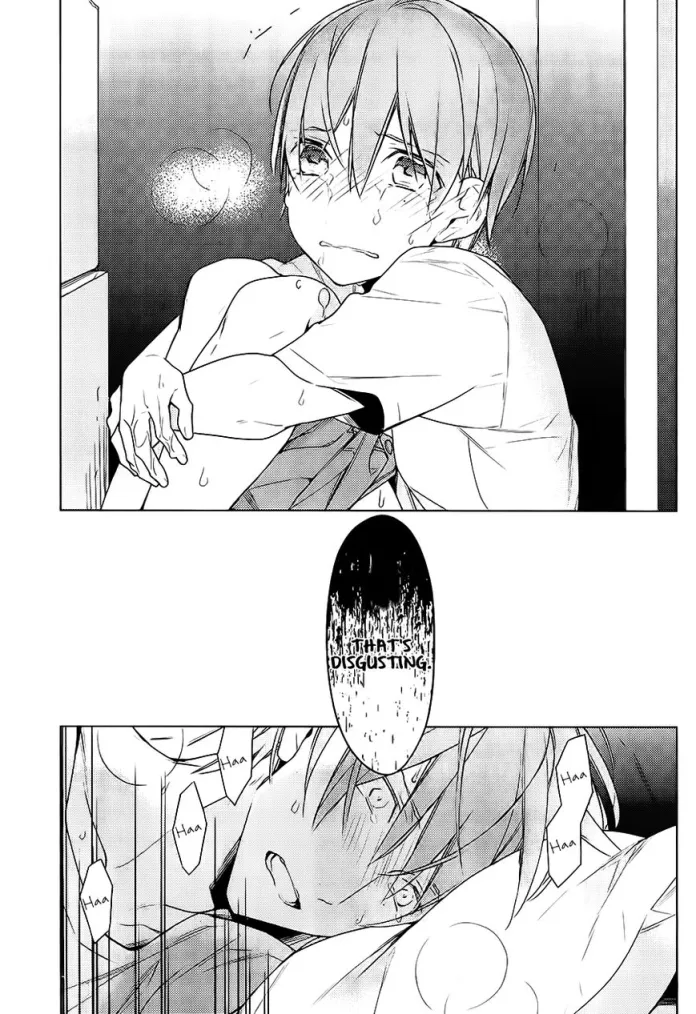

The drama all comes to a head when – homeless, rejected and hopelessly alone – Min Gyeom considers ending his life. Self-harm and suicide are also reoccurring themes in BL stories, often in the damaging context of glamourising abusive relationships. Yet, the strong writing and starkly minimalistic artwork of Raising a Bat make this moment one of real grit rather than cheap shock value. Especially when you take into account that suicide attempts are 4-6 times higher in LGBTQ youth than they are in straight youth, and 8 times higher in LGBTQ youth who come from “rejecting” families – as Min Gyeom does.

“Jade” captures Min Gyeom’s descent into depression beautifully through his subtle changes of expression.

BL can be smutty, endearing, funny, poignant, trashy and fun. What it shouldn’t be is offensive, harmful or insulting to its subject matter or audience. Raising a Bat goes some way in raising the bar on what we should expect from BL, but there’s still a lot more ground to cover yet.

Great analysis! I don’t read yaoi (or much romance at all, actually), but the analysis you’ve provided here is thoughtful and well-explained.

Loved this line: “And why does the only female character in the entire story have to be characterised as a man-eating sociopath?” This is true for so much shonen. I’ve actually written a post about action comics myself, because female characters rarely get the page time they deserve, and when they do, they have no depth or characterization. (If you’re interested: https://natalieschriefer.wordpress.com/2016/04/11/women-comics/) Terribly enough, some of the feedback I received on the article was: “The genre is meant for boys. Who cares if the female characters are poorly characterized? Boys don’t want to read about strong women.” ….HUH?

Anyway, nice post. I appreciate the insight into yaoi manga — hopefully the genre will see the worth of strong female characters soon! Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Natalie! Glad I was able to provide some insight for you. I’ll take a look at your post sometime, it sounds right up my street 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: Viral images | Tainted Love: Fetishizing Disability in Yaoi Manga Ten Count

Pingback: The Future of Female Is Anime: ‘Yuri!!! On Ice’s Director Sayo Yamamoto | Bitch Flicks

Look stop trying to judge things from your western view of the world. The ethnocentricity amazes me. This is our culture and for us, you guys make the world boring by making everything politically incorrect and over analyzing.

LikeLike

Hi Keiji. You make a totally fair point about ethnocentricity, and I’m always willing to admit my ignorance on things like that. What perspective are you writing from, out of interest? However, I won’t apologise for seeking and valuing political correctness in the media I love. Political correctness is just about addressing historical and systemic imbalances and trying to course-correct to better represent marginalized groups in our society and culture. BL is aimed and women and about gay male relationships, so I don’t think it’s ridiculous to ask creators to try and better represent both, and doing so should create richer and more relatable stories because they’ll be rooted in reality rather than stereotypes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Stories are also meant to play a fantasy world of the person telling them. Most of them are not meant to be either realistic or to represent real life values, especially the romantic focused ones are supposed to just tell you about the romance and the story of those two particular characters.

LikeLike

Pingback: Never Smooch the Robot: May ’17 Roundup | The Afictionado

I appreciated this analysis and am agree with your statements. I’ve seen and continue to read sometimes such treatment of female characters (antagonized), and I’m tired of this in BL universe. I don’t really know the reasons or roots of this ; maybe some authors are doing this because it’s easier to make the girl/s the bad guy in yaoi ? Or should we think that they hate their own gender ?

I’m a fangirl myself. Sometimes I’m amused by the way girls are treated in BL because it looks so caricatural, and sometimes it makes me sad for the same reason.

But lately, thanks to Omegaverse (a genre that I dislike), there’s not even need for females anymore : men are able to bear babies lol ! Malpreg, the other level of female-shaming or inexistence in Yaoi !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Girls in yaoi are commonly either bitches or fujoshis who have no respect for personal space. I realised some fangirls can’t stand reading Hetero smut lol. They’re afraid of their own sexuality and genitals so they use yaoi as a relief

LikeLike

Lol It’s actually the contrary, girls that come into and pretend the genre has to have some sort of self insert female characters have a high insecurity problem.

I love being a woman but that doesn’t mean I need to stare at my genitalie for hours admiring when I am attracted to men lol it would be rather creepy actually to do that.

Men have a lot of videogames and ecchi manga with all anime girls cast but no one points that out to men that they should have male characters as well, why then with girls is a direct assault to their character? We should care about giving ladies what they feel more comfortamble with, not force feeding them what we want.

LikeLike

I really like your analysis ! By the way, each 2 months I received BL for free from an editor and have to review them (in french)… I like at these moments saying “There aren’t rapes !” or, the one of the last I reviewed… I began to talk about a female character I really like when we followed her in one chapter (we follow a different character in each chapter) !

So I understand so much when you said it ! Personnally I read BL because they are often good stories (when it isn’t about sex… Good how I hate it when it’s a majority of sex ! It’s also why I don’t like yaoi in one chapter) ^^ By the way, I also read Yuri for the same reason

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gah who the heck wrote “regular couple”. I hate these type of fangirls/fanboys who act like homosexual couples are so special. I can’t stand it when they say yaoi is better than yuri or shoujo. Yes it can be but doesn’t mean other genres can be just as good. Most don’t give a shit about plot and get impatient when their sex service hasn’t come.

Then there’s omegaverse.I like the concept of going into heat but Mpreg? Such a heteronormative thing. Rape is romanticised a lot too

LikeLike

Pingback: A Yaoi manga fan’s ramblings about the genre she loves – Underdog