Originally published for Bitch Flicks as part of their ‘Female Gaze’ theme week, 26th August 2015.

With their starry eyes, cutesy costumes, Barbie-esque features, and catchphrases overflowing with dreamy positivity, the magical girls of the shojo (girls) genre of anime might not seem like the most feminist of heroines upon cursory glance. Yet, the plucky sorceress’ of such cult classics as Sailor Moon can be seen as emblematic of a counter-movement of female action heroes in Japanese culture – the antidote to the hyper-masculinity of the shonen (boys) genre.

This assessment by no means disregards the problems of the magical girl genre – glorification of the traditionally ultra feminine, fetishisation and infantilisation. Shojo characters with their typically doe-eyed innocence can be easily corrupted to cater to a specific male fantasy of virginal femininity. However, the work of the all-female team of manga/anime creators known as ‘CLAMP’ not only combats these issues, but also, as Kathryn Hemmann in The Female Gaze in Contemporary Japanese Culture writes, “employs shojo for themselves and their own pleasure.”

I became a fan of CLAMP – like most people of my age – in the 1990s. As a child, my introduction to the wonderfully weird world of Japanese cartoons consisted of the standard diet for most children of that era: Pokemon, Yu-Gi-Oh! and Dragon Ball Z. Imported, dissected, re-dubbed, and re-packaged to suit the tastes of a western – and more specifically – male audience. But amongst the shouts of “Gotta Catch ‘Em All!” and “Kamehameha!” there was one show that really left a lasting impression on me. It was about a little girl gifted with great power through capturing and using magical ‘Clow’ cards. She wasn’t muscly; she wasn’t self-assured; and she certainly wasn’t male. She was Sakura Kinomoto, the show was called Cardcaptors (Cardcaptor Sakura in it’s original Japanese format), and it was my first exposure to both CLAMP and the magical girl or ‘mahou shoujo’ genre they helped to popularise.

Like most adolescent heroes, Sakura seems hopelessly ill-equipped to begin with, and yet her sheer determination to achieve her full potential sees her through to becoming a magical force to be reckoned with without ever surrendering her loving personality. Rather than conforming to the ‘strong female character’ stereotype that implies that women must act more masculine to achieve truly equal footing with male action heroes, Sakura’s power stems from traits considered more conventionally feminine: love, empathy, and pureness of heart. Even her wardrobe changes into unapologetically girly battle outfits aesthetically reinforce CLAMP’s refusal to bow to a male audiences’ preferences.

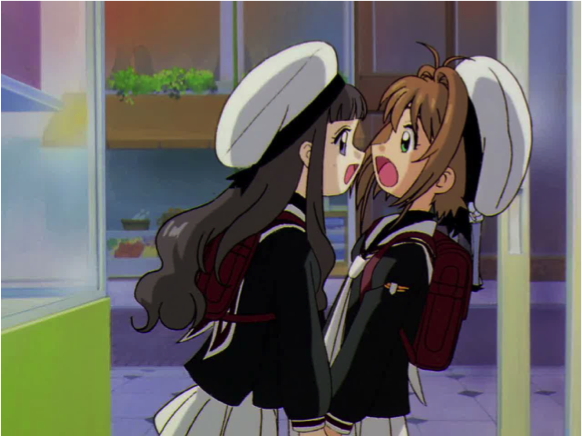

These themes of romance and friendship are a core part of the story development and instrumental in the viewer’s investment in the characters. Through Cardcaptor Sakura, CLAMP explores the complexities of both platonic and romantic female love – both heterosexual and homosexual – from an almost exclusively female perspective. In almost soap opera-esque melodrama, Sakura pines for her older brother’s best friend (who unbeknownst to her, is also his love interest) as Sakura’s best friend Tomoyo pines for her. Tomoyo, who lives a rich and sheltered life in a female-centric household, seems to live vicariously through Sakura. Upon discovering her secret heroics at night, she begins to capture Sakura’s adventures on camera and even provides her with her signature battle costumes, which cause Sakura huge embarrassment. Yet, at the risk of hurting her friend’s feelings, she grudgingly wears them anyway.

As the show develops, we are shown more and more just how deeply Tomoyo’s feelings run. In episode 11, Tomoyo gives Sakura a rare tour of her impressive mansion home, including a cinema room in which she confesses that she watches her recordings back of Sakura in battle constantly. It seems that Tomoyo is as much a part of the audience to Sakura’s life as we – the viewers – are. It also strikes me that this obsessive behaviour might translate entirely differently if Tomoyo were male.

Tomoyo’s idolisation of Sakura is far from veiled, and yet it is not revealed to be unmistakably romantic until Episode 40, in which Sakura must capture a Clow card that makes people dream about their hidden desires. Sakura, Tomoyo, Syaoran Li (Sakura’s rival and male love interest) and his cousin Meilin visit a fun fair. Sakura and Meilin team up to play a Whack-A-Mole game and Tomoyo – as usual – picks up her camera to film Sakura in action. Suddenly, the Clow card appears in the form of a glowing butterfly and lands on Tomoyo’s shoulder. Tomoyo falls into a dream sequence, in which we see her deepest desire play out through her eyes. On a pink background of falling cherry blossom, copies of Sakura dressed in Tomoyo’s outfits call her name and dance playfully around her. We are shown a shot of Tomoyo’s face – staring in awe at first, and then relax into a smile. ‘I’m so happy!’ she says to herself, and runs towards the dancing copies of Sakura – still filming.

It seems like an odd moment to be sexually awakened – watching your crush play a ‘Whack-A-Mole’ game at a fun fair – and perhaps if the show had been targeted at a more mixed audience (or the characters were older) this moment might have been filled with more obvious sexualised content. But through Tomoyo’s own eyes, CLAMP visually summarise the complex feelings of romance, admiration, obsession, and innocent love she feels for her best friend. Not only this, but as Sakura dances continually out of Tomoyo’s physical reach, the implication becomes one of wanting something you know you can never have. Tomoyo knows by now of Syaoran’s feelings for Sakura, and like a true friend, encourages their romance for the sake of Sakura’s happiness rather than her own.

This ‘doomed’ romance trap seems to be a family curse, as we discover in episode 10 that Tomoyo’s mother appeared to also be hopelessly in love with Sakura’s mother (who happens to also be her cousin). Similarly, Sakura’s mother didn’t return her cousin’s feelings as she was in love with an older man (Sakura’s father) in the same way that Sakura is attracted to Yukito – an older boy. Both mothers are absent from their lives – Sakura’s mother through death, and Tomoyo’s through continual business trips – yet their daughters seem fated to play out their romantic histories.

Suffering from a bout of nostalgia, I decided to revisit the show as an adult, first in it’s Americanised form, and then the original Japanese version to compare the differences. I was shocked to discover that in an effort to make the show fit the perceived needs of their rigidly defined demographic of young boys, the executives at Kids WB had hacked all elements of ‘toxic’ feminisation from it – romance, homosexuality, and the agency of Sakura has a protagonist (even her name is removed from the title) – dramatically reducing the series from 70 to just 39 episodes. In fact, if they had been able to “maximise” their cuts, the show would reportedly have run for merely 13 episodes. In other words, there was a concerted effort to twist the female gaze into a male one under the belief that CLAMP’s blend of hyper-femininity and action would be unappealing for the male audience it was being sold to. In Japanese Superheroes for Global Girls, Anne Allison quotes this from an executive from Mattel, “[…] In America, girls will watch male-oriented programming but boys won’t watch female-oriented shows; this makes a male superhero a better bet.”

Whilst moaning about all this to my partner recently, I asked him if he had watched the dubbed version of the show as a child. He said that he had, but didn’t realise until he was older that the show had probably been intended for girls. I asked him if he remembered being turned-off that the show’s hero was a little girl as opposed to the ultra-masculine characters of his favourite childhood anime, Dragon Ball Z. His answer totally undermines Mattel’s assumptions about the show’s gender appeal: “I thought Sakura was really cool. In fact, I loved her so much I begged my mum for roller-skates that Christmas so that I could skate around to be like her.” Even more affirming than this is the fact that whilst the dubbed version of the show ended up being cancelled, the original Japanese one ran to its intended conclusion; spawned two films; and inspired two spin-off series’ using the same characters – Tsubasa: Reservoir Chronicle and xxxHolic.

Sadly, by ‘butching’ Cardcaptor Sakura up to be squeezed into the TV schedule alongside Pokemon and Dragon Ball Z, western children were deprived of the tender and emotionally complex storytelling and character development behind all the magic and swordplay – and even from getting a satisfying ending to the show. It seems that whilst Japanese children are considered mature enough to deal with female superheroes, complex pre-pubescent emotions, and LGBTQ+ representation from a female perspective, western children are unfortunately not treated with the same respect or intelligence.

iwantedwings (aka Hannah) is a freelance writer, artist, anime-nerd, and Britney Spears apologist based in the UK.