Originally published on the Fanny Pack Blog.

There’s no denying that body image is a prickly issue within Feminism and our cultural landscape in general. As women, we live in a confusing world in which certain cosmetic companies *cough Dove cough* tell us to love our imperfections whilst simultaneously selling us products to fix imperfections we never realised we had (dry underarms, anybody?); in which we are apparently dicing with death when we order diet pills from the Internet; and in which our most shamed body parts one month could become our most fantasised about the next, depending on which female celebrity ranks highest on Google.

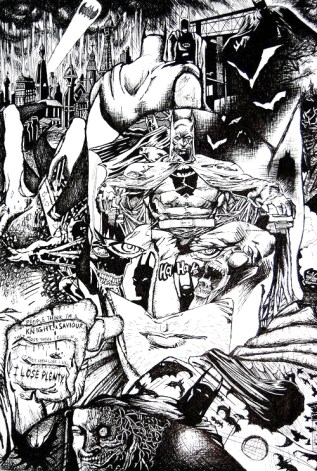

It is no surprise then that our precious imaginary worlds, both on page and on screen also suffer from the same real-world problems. A recent trend happening online that has caught my attention has been identifying and even ‘fixing’ the unrealistic proportions of our favourite super heroines and Disney princesses. From hair, to historical accuracy, to waistlines – if there’s something to be changed, there’s someone with a Photoshop brush poised to change it.

The reason is certainly well-intentioned. These fictional characters – however much we kid ourselves – are intended for the consumption of younger audiences, and as such, impractical standards of beauty can have a negative impact on their perception of it and their sensitive self-confidence. But, does that mean that every ridiculously proportioned female character rendered in ink or animation is a problem waiting to be fixed? I would argue no, or at least, not in certain circumstances.

This thought struck me after I came across this particular image of Wonder Woman from Bulimia.com, whose creative team came up with the idea of giving superheroes ‘realistic waistlines’ after seeing people do the same for Disney princesses.

The incentive was completely worthy: highlighting to young people that these fictional characters sport similarly fictional body shapes. Whilst it’s pleasing to see that adding a few extra pounds has certainly not lessened these super heroines’ appeal in the slightest, I did take issue with this treatment being performed on Wonder Woman specifically, and let me explain why.

I grew up in the late 90s/early 00s glued to the exploits of small-screen action heroines like Buffy and Xena as they high-kicked and shrieked their way through their improbable lives. They may have worn short skirts and metallic bras, but they were, and still are, hugely empowering to me, and their athletic physiques were a big part of that.

As the grand matriarch of all our pop cultural warrior women like Buffy and Xena, Wonder Woman still looms large today as the physical embodiment of female strength; the kind of strength that enables her to go toe-to-toe fearlessly with her muscular male equivalents. She is a warrior, a Goddess, and a champion of women’s rights. She’s the comic book answer to Rosie the Riveter.

The crux of what I’m saying is this: A female character’s waistline has to be as realistic as her job description.

If she was raised on an all-female island of warrior women, then she should have a warrior’s body. However, if she was raised in a fairy tale castle where her only physical activity was to sweep the floor and cook dinner for an ungrateful and demanding surrogate family then there is no logical necessity for her to sport a 24” waist and tiny slipper-sized feet. The same goes for nearly every princess in the Disney school of character design, in which being impossibly slim is as requisite as singing to birds and having at least one dead parent.

Not only can excessively small waistlines be a problem, but excessively sexualised ones too. And whilst exaggerated idealisation can be acceptable for certain characters as I’ve discussed, exaggerated sexualisation is often totally unnecessary and voyeuristic. This usually comes through not in the way that certain female characters are built, but how they are clothed and posed, and one that has attracted a lot of scrutiny recently is Starfire from DC’s Teen Titans.

Like Wonder Woman, Starfire is a warrior princess from a faraway fantastical place and as such she is pretty darn ripped. Her idealised toned body poses no problem to me, and her hyper-positive personality makes Starfire one of my favourite members of the Titans. However, her wrestling-inspired barely-there costume and the leering angles artists often choose to draw her at distract from her ungendered qualities as a powerful crime-fighter to make you constantly aware that she is a woman with very womanly parts.

There is of course nothing wrong with female characters utilising their feminine wiles. Poison Ivy and Catwoman, for example, use the femme fatale shtick as part of their villainous arsenal, and Starfire is in fact a very playful and flirtatious character – she even worked as a model at one point in the 80s. But I refuse to believe that even such a body-confident beauty like Starfire would decide that an outfit that risked her boobs popping out every time she threw a punch.

The Bulimia.com parody artwork was of course not intended to criticise comic book art as a whole, but it did unintentionally hit upon the solution to the problem of unrealistic proportions in fictional characters: Diversity. As I said earlier, if we want our heroines to look more positively ‘realistic’ then the parameters of their realism need to be defined by their individual lifestyles just as we real women are defined by ours. If a female character is a brawler that spends every night kickboxing street thugs, give her a six-pack and killer thighs. But if she’s just rocked up as a new student at the Xavier institute with the power of telekinesis then she could be either over, under, or of an average body weight and it wouldn’t make any difference to her abilities or our ability to connect with her as a character.

Thankfully this positive change towards body diversity is already alive and well in pop culture as exemplified by excellent comics such as Rat Queens and excellent cartoons such as Steven Universe, which both feature refreshingly female-orientated super-powered teams of diversely powered and sized heroines to love and relate to.

In terms of costume, it’s also pleasing to see the small but significant changes made to powerhouse heroines recently like Wonder Woman, Ms. Marvel, and (yay!) Starfire, whose idealised but practical bodies are finally matched by practical clothing.

(From left to right, clockwise) Wonder Woman (2015), Starfire (2015), and Kamala Khan, aka the new Ms. Marvel (2014)

We still need our Goddesses, warriors, and sirens, but there’s more than enough room for our chunky, scrawny, or just plain averagely shaped heroines to inspire us as well.