Originally posted on the Fanny Pack blog on February 3rd 2016.

Well, won’t they?

One of the most enduring myths about homosexuality that it’s opponents cling to dearly is that it’s a choice, and by extension, the threat that it poses to children if this choice is ever allowed to worm it’s way into the developing brains. Rather than considering the idea that external influences only awaken or reinforce existing parts of our sexual subconscious, LGBTQ rights’ opponents often characterise any discussion of sexual orientation in schools or media as a brainwashing toxin of a sinister ‘gay agenda’ seeping into the sensitive minds of the youth – tricking their ‘naturally’ heterosexual brains into pondering devious sexual behaviour.

Frederic Wertham’s 1954 book asserted that Batman and Robin’s “hidden” romance would impact negatively on young comic book readers.

Sexual ‘deviancy’ in adults can apparently be treated with regular visits to your local conversion camp, or simply marrying someone of the opposite sex and suppressing all those unnatural urges to do what comes naturally to you. But before it’s too late, how do you prevent all those liberal influences from ‘recruiting‘ children into homosexuality? In schools, regulation of the curriculum can be very effective. Only twelve states in the US require teachers to discuss sexual orientation, and even more disturbingly: three of those twelve dictate that teachers only impart negative information. In 1988, the UK government passed the now infamous Section 28 amendment, stating that a local authority “shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality”. (This harmful legislation wasn’t repealed until 2003 after years of hard-fought campaigning from pressure groups like Stonewall.)

That leaves the other major influence in most children’s lives: cartoons. Like every other form of mass commercial entertainment, cartoon creators have to continually walk a fine line between cookie-cutter commercialism and original artistic expression; between pleasing their ratings-obsessed executives and staying true to their visions as storytellers. But what do you do when this vision involves a young boy being raised by a group of lesbian alien super-heroines? How much of this vision are you going to be allowed to stay true to before your network bosses start to catch a whiff of that ‘gay agenda’ you’re obviously trying to push on unsuspecting children?

The cast of Cartoon Network’s Steven Universe: (clockwise from left) Amethyst, Garnet, Pearl and Steven

This is a question that ‘Steven Universe’ creator Rebecca Sugar has had to face in the wake of Cartoon Network UK’s decision to censor an episode of the show that recently aired in the UK. You may think I’m joking about the lesbian alien super-heroine thing. I’m not. Three of the show’s main characters form part of an all-female team called ‘The Crystal Gems’ who come from a similarly all-female planet of imperialistic aliens whose personalities and powers derive from gemstones. When one of their members – ‘Rose Quartz’ – falls in love with a male human on Earth, she sacrifices her own body in order to have their half-human, half-gem-powered son: Steven Universe. The Crystal Gems soon adopt him into the team to replace his mother and essentially act as surrogate mothers/aunts/sisters.

Steven’s parents: Rose Quartz and Greg Universe

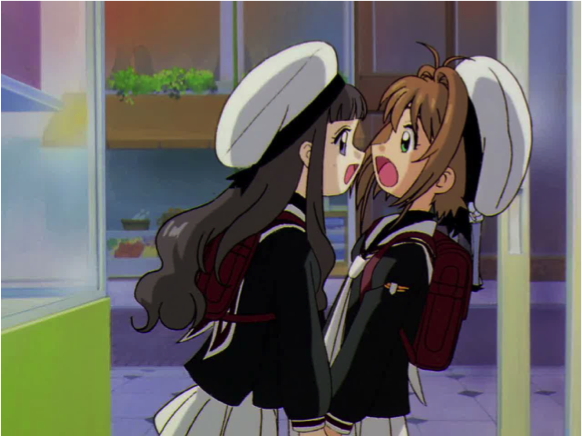

The controversial scene in question comes from an episode in which it becomes clear that one of the Crystal Gems – ‘Pearl’ – had romantic feelings for Rose Quartz. These feelings were only intensified when Rose Quartz started to find herself drawn strangely to Greg. As in typical with Steven Universe, these feelings eventually came to a head in a musical number called ‘What Can I For You’, which is where the censorship comes into play.

Interestingly Cartoon Network US didn’t make the same censorship decision as their UK counterpart, leading to fans of the show creating side-by-side comparisons of the censored and uncensored versions of the same scene:

Two women dancing intensely… Hmm. It’s almost disappointing how un-gay the scene actually is. Following a very vocal backlash online from the show’s adult fans, the network defended it’s decision with this statement:

“In the UK we have to ensure everything on air is suitable for kids of any age at any time. We do feel that the slightly edited version is more comfortable for local kids and their parents. […] Be assured that as a channel and network we celebrate diversity – evident across many of our shows and characters.”

However, as Pink News points out, this decision conflicts with the BBFC’s ‘U’ rating guide (the rating which all Cartoon Network shows for children aim for):

“Characters may be seen kissing or cuddling and there may be references to sexual behaviour. However, there will be no overt focus on sexual behaviour, language or innuendo.”

It’s also notable that this is a repeated decision from Cartoon Network, who also censored a gay kiss on an episode of Clarence last year between what some consider to be the first overtly gay characters in a children’s cartoon. This would have been more of an impressive milestone if it not for the fact that these two men merely served as the punch-line to a joke in the episode about a woman being stood up for a blind date, rather than central protagonists – as is too often the case with any LGBTQ inclusion in children’s media. Subtext and throwaway humour has sadly long been the modus operandi of any writer/animator in order to slip anything ‘covertly’ gay past possible censorship. Other recent examples include Gobber from How To Train Your Dragon 2 and Oaken from Frozen.

Oaken waves to his implied family in Disney’s ‘Frozen’.

What makes Steven Universe different from any other of these examples is that the sexual orientation of its characters is far from throwaway. Just like the mythical island of Themyscira (home of Wonder Woman), all the gems hail from a single-gendered planet meaning that the only romantic relationships they have the option of pursuing within their own species are same-sex ones. Whereas as we live in a hetero-normative society, they live in a homo-normative one. Needless to say the show also passes the Bechdal test with flying colours.

The gems also possess the ability to fuse with one another to become stronger, which they can only achieve through dancing in perfect synchronisation to fuse both body and soul. Some of these fusion rituals are harmlessly flirtatious but others can be more meaningful. For example, it is revealed later in the show that [SPOILER ALERT] the body of the leader of the Crystal Gems – ‘Garnet’ – is actually the result of two gems (Ruby and Sapphire) that fell so deeply in love that they decided to fuse together indefinitely, which quite frankly sounds like the purest expression of marital bliss ever.

Clearly, LGBTQ themes are so core to the underpinnings of the show’s characters that to try and remove even the slightest hint of them – as Cartoon Network did – has a detrimental effect on the nature of the show. This threat was not lost on any of its fans either, as a petition to air the uncensored version of the episode in the UK and Europe has so far picked up over 6,000 signatures.

It seems to me that what Cartoon Network means by “celebrating” diversity actually translates through its actions as ‘tolerating’ diversity. Gay characters can exist as sanitised background noise or pithy punch-lines to straight character’s jokes, but as soon as they become living, breathing protagonists with feelings that children might start to identify with, the executives get squeamish. Sure, they want to pander to the demands of liberal, politically correct parents, but they also have to be mindful of being accused of pushing that ‘gay agenda’ by the more puritanical or conservative parents.

Where is the consistency in living in a country that legalises same-sex marriage but simaltaneously continues to strip same-sex relationships from children’s media as if it is something perverse that they should be protected from?

Why – in the same episode – is this sexual behaviour acceptable:

Rose Quartz and Greg Universe (Steven’s parents) embrace lovingly in the episode ‘We Need To Talk’. This scene aired uncensored.

But this isn’t?

Pearl and Rose Quartz share an intimate moment in the same episode. This scene was censored in the UK.

Studies show that the later children identify as being gay, the more frequently they are bullied by their peers. And with 1 in 2 young people in the UK identifying themselves as being “not 100% heterosexual“, it seems that the more examples of positive examples of healthy, loving, and normalised same-sex relationships they have access to at an early age, the better off their mental health and well-being will be later in life.

Please send a message to Cartoon Network UK that same-sex relationships shouldn’t be censored from children’s cartoons. Sign the petition here.

IMAGE CREDITS:

- Screenshot of Helen Lovejoy from ‘Much Apu About Nothing’, The Simpsons, 1990.

- Cover of Frederick Wrexham M.D’s book ‘Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth‘, 1954.

- ‘Steven Universe‘ banner, Cartoon Network, 2013.

- Screenshot from ‘We Need To Talk’, Steven Universe, 2014-15.

- YouTube clip comparing Cartoon Network US and UK airings of a scene from ‘What Can I Do For You’, Steven Universe, 2015-16.

- Screenshot of Oaken waving to his family from Frozen, Disney, 2014.

- YouTube clip from ‘The Answer’, Steven Universe, 2016.

- Screenshot of Rose Quartz and Greg embracing from ‘We Need To Talk’, Steven Universe, 2015.

- Screenshot of Rose Quartz and Pearl dancing from ‘We Need To Talk,’ Steven Universe, 2015.